Inside Out: Making The Move From Gym To Crag

Not everyone who climbs indoors transitions to rock – indoor climbing is now a sport in its own right, and an Olympic one at that. But as Natalie Berry explains, venturing beyond the confines of an artificial wall is one of the most rewarding moves any climber can make.

My rock climbing journey began inside-out. Twenty years ago, as a junior competition climber and GB Climbing Team member, my focus was blinkered – training and performance on indoor climbs was paramount. I knew that an entirely different world of climbing existed outside of my plastic-focused bubble. Rock climbers made a point of exerting their supposed superiority over indoor and competition climbers: “Indoor climbing isn’t real climbing. Where’s the risk? It’s all about being in The Great Outdoors,” they said – the capital letters implied by the superiority of their tone. But I didn’t understand the subjective hierarchy that they repeatedly tried to impress upon me.

My parents had absorbed the popular narrative that rock climbing was a dangerous activity – for ‘daredevils’ only – and their lack of knowledge and experience heightened their reluctance. Part of me had been dissuaded by my parents’ reticence.

If they were anxious, then surely it was with good reason? I also didn’t see the appeal of getting cold, soaked to the bone and being at increased risk of injury or death - especially not if I could do the same activity in the relative warmth and safety of the climbing wall instead. In addition, the equipment, instruction and travel costs for climbing outdoors were high compared to sticking indoors, and we needed to save money to fund my training and competition costs.

My first taste of outdoor climbing happened aged 10 on a freezing cold and rainy day at a traditional (i.e. non-bolted) crag north of Glasgow. I was accompanied by an experienced climber from the wall and my dad. In my youthful naïvety, I hadn’t prepared for a walk-in (the approach to the crag), which was an uphill slog up soggy, muddy grass. Nor did I realise that there would be no toilet facilities (“Is there a portaloo?” I asked).

As I scrambled up my first and only climb of the day before conditions deteriorated further, I was unimpressed. I didn’t understand why marching up a hill to stand around and faff with trad gear while getting soaked and cold was so enjoyable for some climbers – let alone ‘superior’ to the indoor element. “I could have done ten routes at the wall in the time it took to walk up there and get ready, before giving up!” I complained to my dad afterwards. I’d learned one lesson at least: check the weather forecast and avoid going to the crag on rainy days.

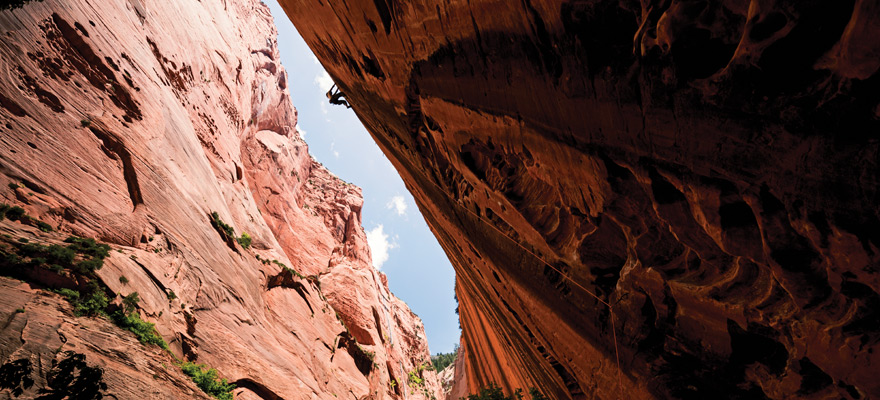

In my teens, I grew more independent and began sport climbing around Europe. The environment was more comfortable, with glorious sunshine, less rain and no midges. The familiarity and security of climbing on bolts rather than faffing with trad gear put me at ease as I gained experience of simply being outdoors. All I required was a rope, a set of quickdraws and a belay device. I learned to read the rock face – arguably the biggest hurdle for newcomers to the outdoor discipline – and added to my movement repertoire.

I travelled to climbing destinations in spectacular settings in Spain and France, where burnt orange and grey limestone cliffs perched on verdant hillsides. But at this point, the beauty surrounding me was simply a pleasing side-show that I largely took for granted. Even outside of the competition arena, the main event was climbing noteworthy routes on famous cliffs, and pushing my physical and mental capabilities. My rock climbing philosophy remained very much ‘inside-out’. It was only really later that my horizons broadened.

During a university year abroad spent in the mountains around Grenoble in France, and in the Austrian Tyrol region, I began to realise that ‘outdoor climbing’ doesn’t just take place within the confines of lines up a cliff. Rather than focusing solely on the next move – as I would with a sport climb - my narrow vision was widening to take in my surroundings. As I started to shed my competitor’s ego and look more closely at the world around me, time appeared to slow down.

I simply enjoyed being outdoors for the sake of being outdoors. There was no-one to beat, no rules, no schedule to follow. Even trudging uphill to the sport crag became a treasured activity and part of a day’s adventure. I felt a long way from home geographically and culturally, but I was more self-assured and open to new experiences than ever before.

Today, I love the fact that sport climbing on rock forces me to observe and appreciate my surroundings. I now understand that a good day at the crag is worth more than the sum of its parts. I no longer perceive the environments in which I walk and climb as theatres for personal performance, but as an integral part of our planet’s heritage and future.

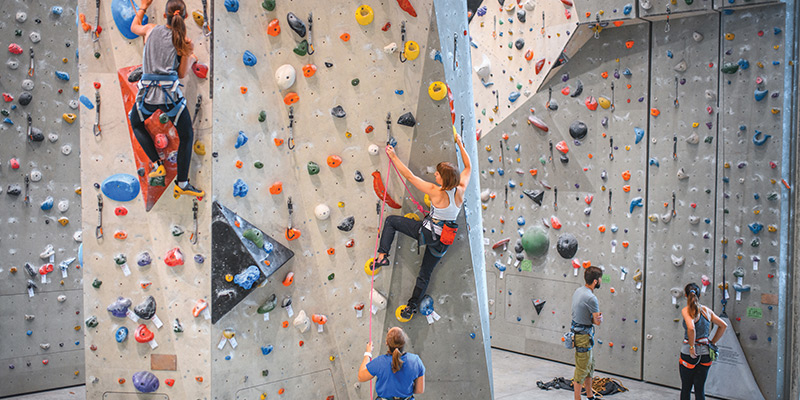

Without my early introduction to climbing through the indoor discipline, I most likely wouldn’t have discovered rock climbing and the outdoors in general. In recent years, the boom in indoor walls has made climbing more accessible and democratised the sport, helping people to develop skills that can be transferred outside in order to expand their comfort zones, travel and connect with nature.

Yet unlike the vocal old-school proponents of rock climbing, I don’t consider climbing outdoors to be superior to the indoor element. After all, the best climber is the one having the most fun — no matter the medium. ‘Real climbing,’ I’ve come to realise is whatever makes you happy, whether that’s on rock or plastic.

HOW TO MAKE THE MOVE TO OUTDOOR SPORT CLIMBING

Some walls advertise transition to rock courses at local crags. Alternatively, search for a local qualified instructor on the Mountain Training website.

For more information on learning to climb in the UK, visit British Mountaineering Council. Natalie Berry is the editor of UKClimbing.com, and an Ellis Brigham ambassador. Follow her @natalie.a.berry.