Tech Talk | The New Ice Age: History of Ice Axes

Creative Director Dave Whitlow began working in our Liverpool store as a Saturday lad in 1975. Since then he’s witnessed first-hand the astonishing evolution of ice climbing – and the equipment that’s made it possible.

How did the earliest ice axes you sold work?

The adze [shovel] would cut steps. The spike element – the pick – on the other side was really an arresting tool. If you slipped you'd put your weight over the pick and that would break your fall. The length and the spike on the bottom was essentially a walking stick. It was a development of the very earliest 'alpenstocks', which were long wooden poles with a spike on the end, used by the first people to climb Mont Blanc and the other big alpine peaks.

With an ice axe like the classic Stubai Aschenbrenner you could probably climb ice of up to about 60 degrees, and cut steps into it. But it became really difficult, and as climbers started to want to climb steeper ice, the tools had to develop to facilitate that.

Ellis Brigham has supplied Stubai ice axes since the 1950s.

What's the idea of curved picks?

When you swing it and stick it in the ice, it stays there. It grips. You can pull on it and it actually extracts quite easily as well. Alongside crampons, it enabled people to use what they call a front pointing technique. Prior to that they would be cutting steps and crabbing sideways. Now you're literally facing the ice with four points of contact; ice axe, ice axe, step, step. It was a radical advance, and step cutting became a thing of the past.

Which brands pioneered this movement?

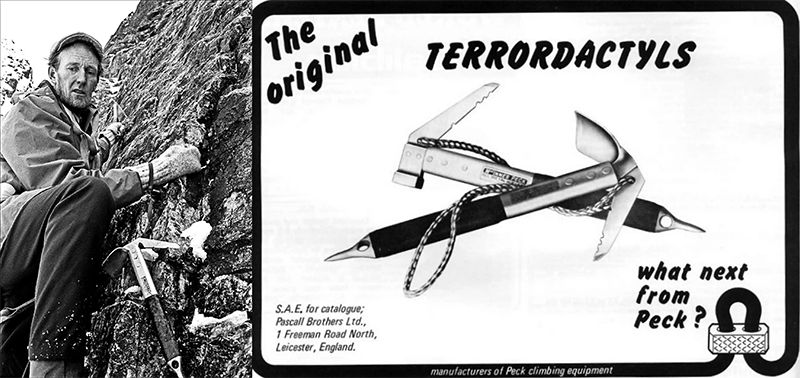

The Chouinard Zero made a big noise. [Patagonia founder] Yvon Chouinard actually visited Fort William in the 70s and climbed with local climbers like Hamish MacInnes, and the influence went both ways. They were at the cutting edge of what you could do with winter climbing, constantly questioning what were really quite primitive tools in those days. Chouinard's approach was to curve the existing tools that were out there and ultimately come up with his own ice axe, but Hamish MacInnes had a different route: he developed an all-metal tool called the Terrordactyl. It was much much shorter, 40-45cm long, and had a dramatically inclined straight pick. Both tools had their advantages and disadvantages.

The Terrordactyl was particularly good at Scottish mixed climbing, where you're in very confined areas – often iced-up gullies – and the terrain includes a lot of frozen turf and shallow placements. The downside was it rapped your knuckles quite badly because there wasn't much natural clearance; bloody hands became part of the game. Chouinard's more elegantly curved pick excelled on big open alpine faces. But they both inspired where the whole story of ice tools went from there.

Hamish MacInnes and his radical Terrordactyl

How did the materials evolve?

Wood was heavy but had the advantage of absorbing vibrations really well, and for a while Chouinard experimented with bamboo, which was very light, but the downside of all the wooden shafts was that they reached a critical point where they would break under a climber's weight, and if they were used for a belay anchor point, they could potentially fail.

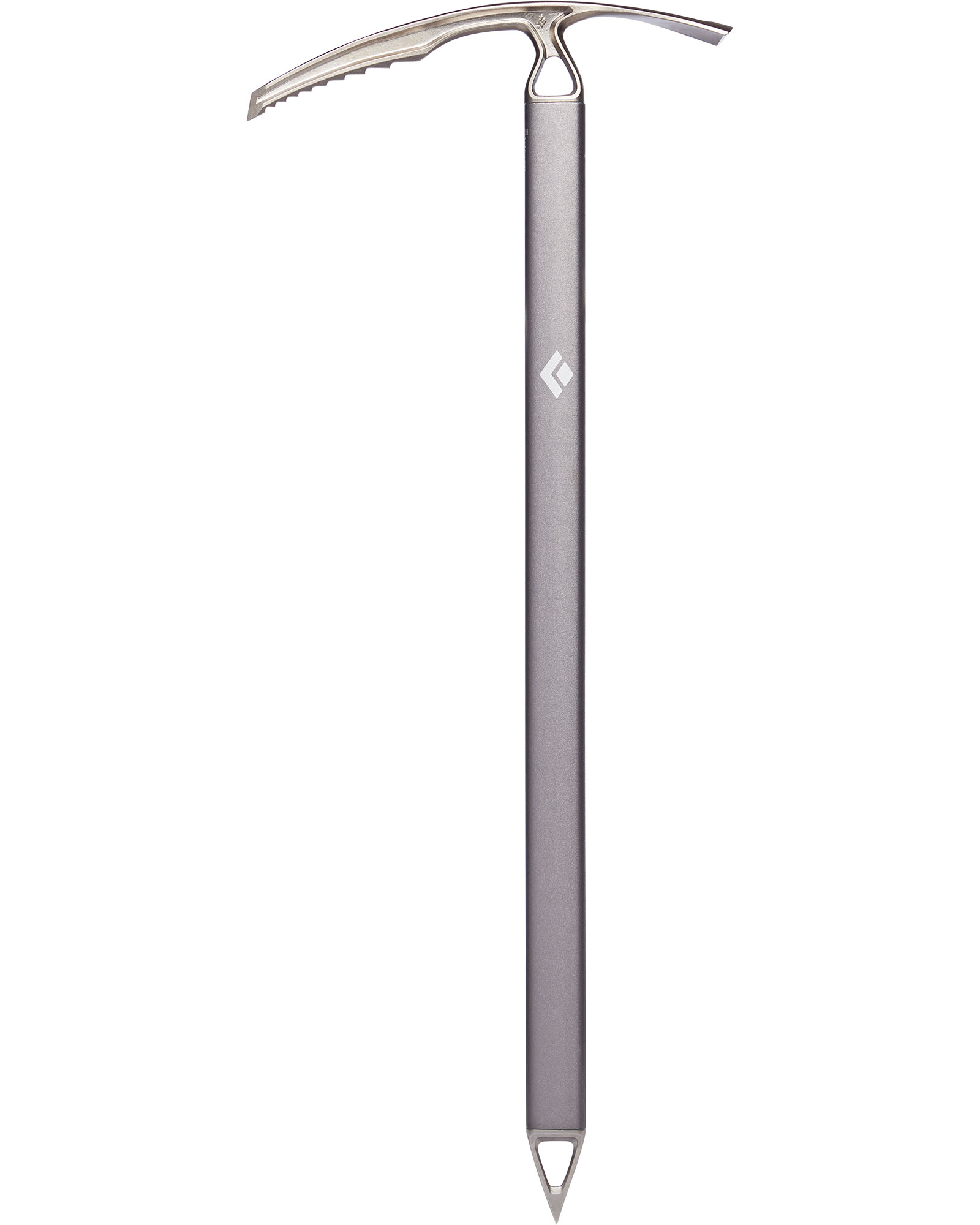

Eventually the whole equation swung over to the metal camp because it was safer. Some of the early models were solid metal and prohibitively heavy, but after that they became tubular, and these days they use aircraft grade aluminium or lightweight alloys.

What was the next big innovation?

The big game changer was an ice axe developed by French company Simond called the 'Chacal' – the Jackal. It was the first time the pick was curved in the opposite direction. With this reverse banana shape you could climb really steep ice like you could with the Terrordactyl, but it was a much more elegant tool to use in the hand. Ice tools had always been quite brutal instruments – chopping and hammering – but this thing didn't need as much force; it started to make ice climbing more delicate and finessed, and that in turn enabled people to climb steeper and more marginal conditions, where the ice is thinner.

Did no one patent this technology?

Seemingly not, since pretty much all technical ice tools have that reverse pick design. I don't know if it was an altruistic thing, but everyone in those days got on in the climbing world – as they still do. Taking advantage of patenting an idea and restricting development just wasn't on, I suppose.

Talk us through a cutting edge design like the Petzl Nomic.

The next major development from the Chacal was to curve the shaft of the ice axe as well, which perfected the swing. Then people on the steepest climbs wanted to go leashless. Previously a leash would go from the ice axe head to your wrist, but as people started to switch hand to hand and reach higher, the curved shaft started to develop a recessed handle – like the one you see on the Nomic – and there's no [built-in] leash. It allows more reach, more elegant placement and a lot of penetration without as much brute force. You'll combine this with a safety leash, which is a semi-elasticated bungee you can clip from your harness to the bottom of the ice tool rather than the head.

Like the Chacal, the Nomic is modular, so you can adapt the pick to different genres of ice climbing. You can add different weights, too, which alters its balance. On the back of the head you have the last remnants of the hammer, so you can use pegs if required, and on the bottom is a pared down version of the original spike, for when you're walking.

So, where do we go from here?

It's hard to say. Right now, people are climbing pretty much at the cutting edge of what's possible. I guess the only way to improve is to go lighter, perhaps more carbon fibre solutions. It's only 70 years since the Aschenbrenner, but where they're at now with these modern tools is a million miles away, and the terrain they're climbing is so steep and radical.

The next development is probably in the physique and mental strength of the climber, and their ability to push it out there further. Only when the technology isn't sufficient to match the aspirations of that climber – today's Chouinard or MacInnes – will they know where to take it. But the great thing with these modern tools is that they do elevate a run-of-the-mill type climber to something a little bit better; they allow people to climb steeper and harder terrain a lot easier, and make the whole experience a lot more pleasant.