Discover Backcountry: Avalanche Safety Basics

We sat down with Henry Schniewind from Henry’s Avalanche Talks to get some do’s and don’ts when it comes to keeping safe in the backcountry.

In 90% of avalanche accidents, the slide is triggered by either the victim, someone in their group or someone above them. It is almost always a dry slab avalanche that is triggered by people present, not a spontaneous wet snow avalanche that comes down from above.

This is good news, because it means that we are in control. We can manage the risk. If we make good choices we can keep it safe. If we make bad choices we need to remember this quote from Bruce Tremper: “We have already met the enemy… it’s us!”

Off-piste comes from the French ‘hors-piste’: hors which means ‘off’ and piste which means ‘path’. So, when you are off-piste, you are by definition ‘off the beaten path’. In our discussions, off-piste and backcountry refer to unsecured areas. Backcountry can refer to more remote areas than off-piste, but here we will describe remote areas as ‘touring’ i.e. areas where a person needs to walk more than 30 minutes to access. For an adventurous person, venturing off-piste and touring is where it’s at. It touches the pioneering instinct. It brings us in touch with nature and with ourselves. This is what makes it fun.

It’s important to know where the secured places end and the unsecured places begin. The resorts do not engage in avalanche control in unsecured areas. It’s not that you will always trigger an avalanche once you venture out of secured areas, it’s just that this is where you start taking responsibility for your own safety.

SO, THE BIG QUESTION IS… IS IT SAFE OUT THERE?

The answer is, it depends. It depends on...

1. WHERE YOU GO AND WHEN

Slope angles matter. Avalanches in Europe don’t release on slope angles less than 28° (about where black runs begin or a very steep part of a red run). In the cold continental climates like North America the minimum angle is 25°. The international avalanche safety community has determined that slopes of steepness of less than 30° will not release a slab avalanche of any consequence to us.

So, to simplify matters, the key threshold is now set at 30°. A slope less steep than that will not release a dangerous slab avalanche, but there is a difference between where the avalanche releases and where you actually trigger it. The trigger happens under your skis, but the avalanche frequently releases above you. Remember, you can be on a low angle slope and still trigger an avalanche that releases on a steeper slope that is above you. So, slope angles are critical to think about when you’re deciding where to go.

Snow stability is important. When the snow is stable it takes more than one person to trigger a release. When the snow less stable, then just one person can trigger a slab. Plus, there is more of a chance that the slab will release above you, making the consequences that much worse.

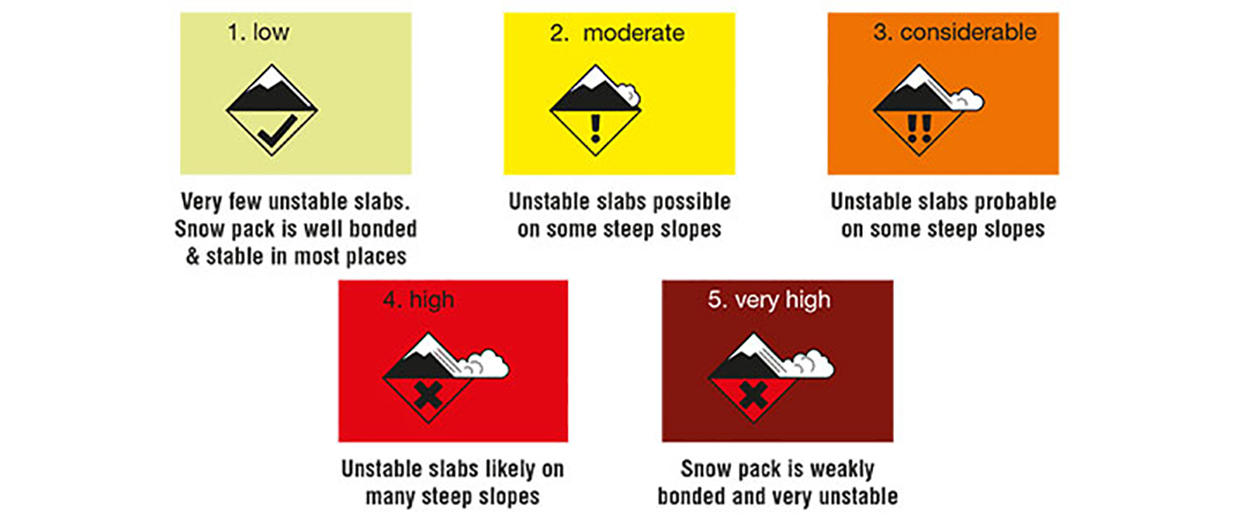

Avalanche forecasts tell you about snow stability. Reading or listening to the avalanche forecast is essential to understand the risks for the day. It includes a danger rating. To use the avalanche forecast, you must understand the definition for the ratings. You also need to get an idea of where the instability is most acute on that particular day. We do this every day before we go out.

Ask local professionals (piste patrol, guides and instructors). Even off-piste and avalanche experts do this. You should do it every time you go out. You might learn something that saves your life.

Start out on low angle slopes and look for clues. Listen for settling and whoomphing (that’s a sound the snow makes when it settles). If you hear it, this is very clear message that the snow is unstable (don’t worry if you’ve never felt or heard it… when it happens you’ll know). Recent avalanche activity is a great clue. If lots of slopes that face one direction have recent slab avalanches on them, you can expect slopes with similar aspect and similar altitude to be unstable. If there is not a lot of recent avalanche activity around and you do not see or hear any other clues of instability and you have understood the bulletins, you can think about exploring steeper and more varied terrain.

2. HOW YOU GO UP OR DOWN

Once you have decided where to go, your conduct on the slope will determine your safety. If you follow the rules and keep thinking, you have a much lower risk of triggering an avalanche. If you do not, you could turn a slope that professionals would regard as offering a safe passage into a very unsafe place to be.

Terrain traps may exist below you. Remember this is where you could end up if something is let loose above you. Will it take you into a hole, a ravine or a lake? Will it take you over a cliff? Terrain traps are anything below you that could make the consequences of being swept away even worse. Terrain traps can transform a small avalanche into a fatal one. This is the most important and clear accident prevention point along with the 30° rule.

Go one at a time on exposed parts of the mountain. Do this wherever slopes above and/or below are steep enough to avalanche. This is one of the golden rules of off-piste/avalanche risk management. The weight of one person is much less likely to trigger a slide than that of two or more people. And if the worst happens, only one of you will get caught and the rest of the group are able to organise a rescue. When we go on a low angle slope and there are no steep slopes above us, we don’t go one at a time. There is no reason to. However, once we get into areas where there are 25° slopes, we know that there will be steeper and shallower slopes around us. Then we make sure that we only ever expose one skier at a time to any risk.

Only ever stop at islands of safety. These are places where you are protected from potential risks, such as under a rock, on a ridge and not below a loaded slope (nothing dangerous above). Ridges are good places to go to whenever you have the slightest doubt. Riding along a ridge is generally a pretty safe bet as long as you don’t ride out onto a cornice above a big drop-off. A ridge doesn’t have to be a classic knife-edge. It can be a rounded area, often referred to as a shoulder. The key point for avalanche safety is that it shouldn’t have a significant slope above you that could release and sweep you away.

Avoid convexities. This is where the slope goes from flat to steep abruptly. A lot of slabs fracture here due to a higher amount of traction stress in these areas. Try bending a Mars bar, the chocolate layer cracks at the convexity (where it bends) because that’s where most of the stress is concentrated. That is a lot like the snowpack on a slope where there are convexities.

Keep your tracks together. The merits of this may not be proven scientifically, but if you follow next to the track of the person who went in front of you and they didn’t set off an avalanche then the chances of you triggering an avalanche are much reduced. Keeping your tracks close together is also good manners as it preserves fresh lines for other people. It is a kind of an ethical thing mixed in with respect for the mountain.

Don’t trigger avalanches on other people. This is really bad form and you’ll go to jail if you kill them.

Always have escape routes in mind. If you are a really good skier, you can sometimes ski out in front of the avalanche and then get out to the side. But recognise it’s very, very difficult to get out of a moving avalanche. Have a plan, but remember most of us will not succeed.

3. HOW WELL PREPARED YOU ARE

Start thinking You need to be well prepared, especially for a self-contained search & rescue.

Start thinking early. By talking with your friends about where you are thinking of going; get an idea of the ability level of the people in the group; find out if they are willing to play the game the way you want to; what is the group tolerance for risk? Is there someone in the group who is going to be pushed beyond their limit, then fall and cause you to spend time in places that might be a danger to the rest of the group?

Know how to use your equipment (transceiver shovel, probe). If you are still alive when the avalanche settles down you have 15 minutes to live. If your friends have this equipment and know how to use it, then they should be able to find you in less than 15 minutes.

Manage your group size. Three to five people is a good number for a group of friends skiing together.

Watch the human factor. Most accidents are predictable. Often mistakes or bad judgement were responsible and bad judgement comes about due to the human factor. Examples of the human factor are: Passion: “If we don’t go on that slope now it’ll all get skied out”; Stubbornness: “we’re going to ride that slope no matter what today”; Ignorance: “What? I had no idea”

SO... IS IT SAFE OUT THERE?

In the off-piste, if you think about where to go and when, how to go down or up a slope and how to be well prepared, you should be fine. You may be close to danger at times, but at least you are aware of it and therefore can avoid it.

On nice slopes with fresh powder there is always a risk, but if you are aware of it then you can manage the risk and make off-piste about as safe as driving your car to work and much more fun.

Henry Schniewind’s website www.henrysavalanchetalk.com is a great resource for all your backcountry safety information.